Guyside: Do you have recovery time covered in your exercise?

Yoga. How hard can that be, right? Just a bunch women accessorizing and lying around on mats, right?

Uh-uh. As I type this, my large thigh muscles are complaining, and my abdominal muscles are providing harmony vocals. All this after an “ambitious” session of Kundalini yoga on Monday. As in so many instances, my pain is my fault, for two reasons:

- I have had a fairly indolent fall, with not nearly the same level of activity — yoga or otherwise — that I might expect normally.

- Being reasonably competitive and interested in seeing what others were doing in the class, I wanted to show that I wasn’t some Kundalini newbie. So I pushed myself.

And here I sit, waiting for my muscles to stop being mad at me.

Time was that such foolhardiness on my part wouldn’t have been NEARLY as big a deal. Gluttony, sudden spurts of exercise, alcoholic overindulgence, nights with very little sleep — it all was part of the game, and I (or at least I think) was able to perform quite fine under all sorts of self-imposed constraints. Now, it’s a different story. I can have late nights, but there will be a price to pay. The days of 80-chicken-wing sprees accompanied by pitchers of beer? Gone. And as my yoga experience has shown me (not for the first time), I need to gauge my level of effort when exercising and prepare for recovery time.

And it’s not just me. Science says so. An article in the Encyclopedia of Sports Medicine and Science states baldly that “The recommended dose of exercise should do no more than leave the participant pleasantly tired on the following day. Recovery processes proceed slowly, and vigorous training should thus be pursued on alternate days.” And a Harvard Men’s Health Watch article points out (too late for me this time) that it’s best to “Work yourself back into shape gradually after a layoff, particularly after illness or injury.”

This week, I brought my bike in from the garage to set it up for winter training. If I have learned one thing from Monday’s yoga class, it’s that while I can do stuff, I can do stuff better if I do it with an eye to gently bringing myself up to speed, rather than exploding out of the gate.

And the benefits of physical activity are so great and diverse that there’s no argument against moving a bit more. Now, can someone pass the Ben-Gay?

Photo: cc-licenced image from Flickr user Jamie Ramos.

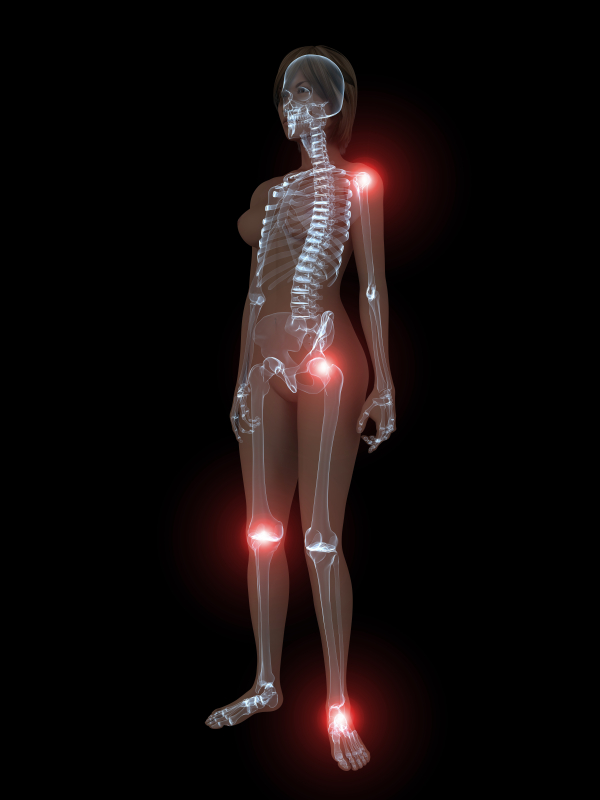

Read MoreAchy breaky joints

Are you consistently achy? Have you been told that you have fibromyalgia? According to research published in Maturitas, not only are middle-aged women prone to achy muscles and joints that might be otherwise known as fibromyalgia, but, those aches and pains may actually be related to hormonal changes. Indeed, when they reanalyzed information collected from over 8,300 women between the ages of 40 and 59, they learned that muscle and joint aches during this time period were significantly related to menopausal symptoms — not only did more than half of the women (63%) suffer from muscle and joint achiness, but, it appeared to double in prevalance in women ages 55 to 59 compared to their younger (40 to 44 year old) peers. Moreover, it tripled in women who were five years into menopause compared to the same group of women.

Are you consistently achy? Have you been told that you have fibromyalgia? According to research published in Maturitas, not only are middle-aged women prone to achy muscles and joints that might be otherwise known as fibromyalgia, but, those aches and pains may actually be related to hormonal changes. Indeed, when they reanalyzed information collected from over 8,300 women between the ages of 40 and 59, they learned that muscle and joint aches during this time period were significantly related to menopausal symptoms — not only did more than half of the women (63%) suffer from muscle and joint achiness, but, it appeared to double in prevalance in women ages 55 to 59 compared to their younger (40 to 44 year old) peers. Moreover, it tripled in women who were five years into menopause compared to the same group of women.

About 16% of these women said that their symptoms were severe or very severe. And importantly, these women tended to display so-called epidemiological characteristics, things like lower socioeconomic status (and by default, less likely to have the means to pay for better healthcare) or a history of psychiatric care. Regardless, there also appeared to be a direct correlation between feeling less healthy and having severe muscle and joint aches. And, women who had surgical menopause carried an even higher risk of presenting with worse joint symptoms.

Study findings also showed that the more intense menopause symptoms were, the more severe muscle and joint aches appeared to be; up to 60% of women with severe vasomotor symptoms also reported severe to very severe aches and pains.

It is possible that the central nervous system has some sort of role, as it impacts both symptoms and joint and muscle pains. Another commonality is that among women with fibromyalgia, symptoms like weakness, anxiety and insomnia — also seen during menopause — are present.

So where are the holes? Because of the study design, there is no cause and effect conclusion at play; in other words, researchers can’t unequivocally say that menopause causes aches and pains. Moreover, the tools used to evaluate muscle and joint pain are actually the same as those relied on to evaluate menopausal symptoms, which means that accuracy may come into question. Still, what they did learn is that hormone therapy reversed or lessened pain severity, meaning that menopause does appear to play some sort of role.

Meanwhile, if you are feeling especially achy and you are in the throes of menopause, it is very possible it’s not in your head. Talk to your practitioner, And consider mind-body strategies such as meditation, QiGong and yoga, which have been correlated with reductions in pain.

Read More