Hot flashes.

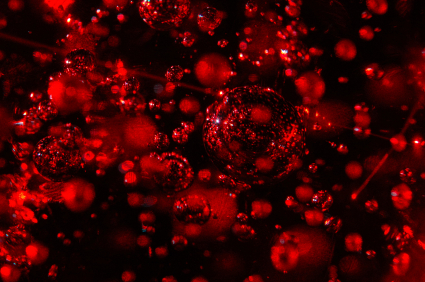

Does anyone really know what occurs in the body to cause the sudden surge of temperature, the licking of the of the internal flame and the momentary feeling that those droplets of sweat dripping down your face are doing NOTHING to alleviate the heat that is emanating from every pore of your body?

Evidently, researchers are coming closer to discovering the ‘why’ behind the flash. And the reason that this is so important is that when medical experts discover the why, they are then one step closer to figuring out how to fix it.

So, let me tell you what’s what.

As I wrote just last week, experts believe that hot flashes are related to a dysfunction in a process called ‘thermoregulation;’ this is the ability to keep our body temperature in a steady state, even when the environment changes. A decrease in estrogen levels, coupled with increased activation of the sympathetic nervous system (which assists in controlling the body’s functions and the fight or flight mechanism) narrows the natural comfort zone and tolerance for temperature fluctuations. Voila! A flash is born.

Hold on. In a new paper published in the open access Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Dr. Naomi Rance from the University of Arizona College of Medicine explains that while the surface of the skin may feel hot during a hot flash, if one was to measure the internal core temperature, it is not even elevated. Rather, she and her team have identified a role that a group brain cells know as KNDy (kisspepti/neurokinin B/dynorphin) may play. These cells are located in an area of the brain — the hypothalamus — that controls metabolic processes related to the autonomic nervous system, including body temperature.

Dr. Nance and her team have only studied the KNDy neurons in rats so far, but what they’ve found is interesting: when they created a model to mimic menopause by withdrawing estrogen, they found that the KNDy cells response is extreme – they grow extremely large and manufacture greater amounts of neurotransmitters that communicate to the part of the brain that regulates body temperature. More communication equals more signalling that the body too hot and needs to release heat. The result? A hot flash and lots of vasodilation and sweating. But here’s the rub: when they measured the temperature of the tail skin in rats with normal KNDy neurons versus those who neurons were shut off, they found that their skin temperature was lower, even with the depletion of estrogen.

While these findings are not yet specific to women, they do show that the KNDy neurons appear to play an important role in regulating skin temperature and its reaction to signals that ‘it’s getting hot in here.’ Perhaps the silver lining is that if they can take it one step further and figure out how to positively control the KNDy cells in humans, they may be able to influence thermoregulation and literally stop those flashes before they start without affecting our real core body temperature.

Stay tuned!